Introduction

The Battle of Towton is usually regarded as:

“The largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil.” English Heritage 1995

But is this really correct … or should we cross-examine the available information?

Many works have been written on the subject “Blood Red Roses” (eds. Fiorato et al 2000), “Towton 1461” (Gravett 2003), “From Wakefield to Towton” (Haigh 2002), “The Battle of Towton” (Boardman 1994), “Yorkshire Battles 1971” (William Hebden), “The Battlefields of England 1950” (A.H. Burne).

In 1762 when Hulme wrote his history of England, Towton was briefly described for its importance of placing Edward IV and the House of York on the English throne. But the ambiguities inherent in the earlier texts were not elaborated upon. The Battle was regarded as something of an enigma. It was little understood. Nobody dwelt upon it and in some respects it was almost forgotten. Even today, it is not widely known about.

Half a century later, however, the first modern description of the Battle of Towton was written by Whittaker (1816) – and following his new interpretation Palm Sunday, 1461, would not be seen in the same light again.

Highlighting the accepted history

Since the early nineteenth century, almost without exception, those historians who have attempted to give a detailed description of the conflicts that took place between Ferrybridge and Tadcaster in March 1461, suggest or state the following sequence of events.

- On the 27th or the 28th of March there was a conflict or conflicts at Ferrybridge where Lord Fitzwalter was killed.

- Later the same or following day, on the 27th or 28th March, at a conflict at Dintingdale near Saxton, Lord Clifford was killed.

- The following day, being Palm Sunday the 29th of March, at the main battle of Towton, amongst many others, the Earl of Northumberland and Lord Dacre were killed.

- Following the battle on the Sunday, there was a rout to Tadcaster and York, where a great many additional people were killed. On the Monday, the day after the battle of Towton, Edward, Earl of March, future King Edward IV, travelled to York to be accepted as victor.

- The battle at Towton and the rout that followed (not including the conflicts at Ferrybridge and Dintingdale) are believed to have resulted in the deaths of 28,000 men.

This has led to many popular beliefs.

- The conflict at Towton was the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil

- The conflict at Towton had a duration of 10 hours

- Over 100,000 combatants (possibly 4% of population) took part in the conflict at Towton

- The conflict at Towton resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 36,000

But …

- If the conflict was so large then why is there such a scarcity of relevant contemporary literature?

- Why was it not more widely discussed at the time? Why are there so many problems with the data? For example: how could a medieval battle have lasted ten hours?

- How could a single medieval battle have resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 36,000 people, similar in number to those killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme with machine guns and cannon?

As the Battle of Towton has been regarded as somewhat of a conundrum for over a century, several authors have summarised these difficulties thus:

So confused are the accounts of this battle, that it is impossible to give a full and particular account of it. Many of those who have attempted to describe it, instead of representing the several circumstances, have given only an indistinct idea thereof. Grange (1893).

Towton is an important battle which is singularly ill-served by its source material “[Some] writers merely mention the battle or, if they do more, mix up their account of it with the fight that took place at Ferrybridge the previous day”.English Heritage Battlefield Report: Towton 1461 (1995)

The “battle of Ferrybridge” was somewhat of a dilemma for chroniclers in so much as most of the writers who considered the matter, and sadly there were few of them, failed to appreciate the sequence of events that were taking place so far north. In fact some authors could not differentiate between the battles of Ferrybridge and Towton, unaware even that they occurred on different days.Andrew Boardman (1996)

Many of these anomalies arise because the three conflicts, at Ferrybridge, Dintingdale and Towton, have been interpreted over the last 200 years as having been fought on different days.

If however, it is considered that the conflicts were all fought on a single day, as one long running battle, then much of the ambiguity disappears and a more reasonable interpretation is possible.

Additionally, attempting to keep an open mind, and looking at the sites archaeologically … do these artefact assemblages represent two separate and isolated conficts … or do they represent one large, moving conflict ?

It is proposed that a number of authors, beginning with Whitaker in 1816, misinterpreted the preceding historical texts and set in motion a situation whereby everyone else followed his lead and did not consult or fully understand the primary evidence. It should therefore be considered that:

- The Battle of Ferrybridge was fought on, what we would now perceive as, the same day as the Battle of Dintingdale, and the Battle of Dintingdale was fought on, what we would now perceive as, the same day as the Battle of Towton.

- Essentially, all three conflicts might have been fought on the same day, or more correctly, within the time frame of less than 24 hours, on a day that we would now perceive as being Palm Sunday, 1461.

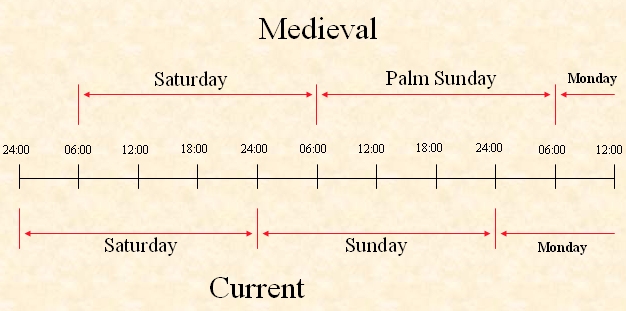

This interpretation is only possible if the timeframe used by medieval chroniclers is different to our own.

We know that the medieval calendar was different to ours as it was changed in the 16th century to the Gregorian system to allow for discrepancies now alleviated by the introduction of the leap year. For example, the 29th March, in 1461 (Julian calendar) would now be 10th April (Gregorian calendar). However, the medieval day (based on the Roman system) was also different. Although it was divided into twelve hours,

- the first, hora prima, began at sunrise

- the last,hora dou-decima, ended at sunset

The night was divided into eight watches – (Ivespera, Prima fax, Concubia and Intempesta before midnight; Incinatio, Gallicinium, Conticinium and Diluculum ).

The common use of the clock in the later medieval and early post-medieval periods, allied with the increasing use of astronomical observations, changed our concept of when the day began.

The medieval day began at dawn or “Prime” (6.00 am) and not at 00.00 hours or midnight as it does today.

Palm Sunday 1461 began at dawn on 29th March (medieval date and time).

Any events that took place before dawn occurred on Saturday 28th March (medieval date), i.e. 5am on our Sunday morning was in fact still Saturday in the medieval period.

If all of the primary sources are read in sequence it becomes apparent that 19th and 20th century interpretations do not comply with these texts, as they have not taken into account the differences in time.

A selection of the primary documents will now be used to discuss the latest interpretation. The relevant parts of each document have been selected in order to clarify the subject

(Review the quotes from different authors by clicking on the arrows below “1 of 12”)

How many people were killed in these three conflicts?

When the medieval authors were writing their comments were they discussing the numbers in terms of thousands or … hundreds?

Referring to hundreds and not in thousands is not that unusual, even today. For example, today we still refer to the year 1996 as 19-96. We are therefore referring to 19 hundreds and 96, and not 1 thousand 9 hundred and 96.

To what does this quote refer,

“…in this way was carried out the skirmish that lasted from twelve o’clock midday until six o’clock in the evening, and there died, as many on one side as the other, more than three thousand men.” Jean de Waurin, 1461 (Hardy and Hardy, 1891, translated by S. and C. Sutherland)

If virtually every contemporary author referred to the engagement by the phrase “following the battle at Ferrybridge”, is Waurin also referring here to all three engagements? Did the deaths from all three conflicts total only 3000 in a similar manner to all other Wars of the Roses conflicts?

The conflicts at Ferrybridge, Dintingdale, and Towton are probably Britain’s longest medieval conflict. Whether the death toll was 28 hundred or 28 thousand, it was still seen, at the time, as a very large conflict. However, the Battle of Towton alone, was almost certainly not,

“the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil”